8.2 Cryptographic Building Blocks¶

We introduce the concepts of cryptography-based security step by step. The first step is the cryptographic algorithms—ciphers and cryptographic hashes—that are introduced in this section. They are not a solution in themselves, but rather building blocks from which a solution can be built. Cryptographic algorithms are parameterized by keys, and a later section then addresses the problem of distributing the keys. In the next step, we describe how to incorporate the cryptographic building blocks into protocols that provide secure communication between participants who possess the correct keys. A final section then examines several complete security protocols and systems in current use.

Principles of Ciphers¶

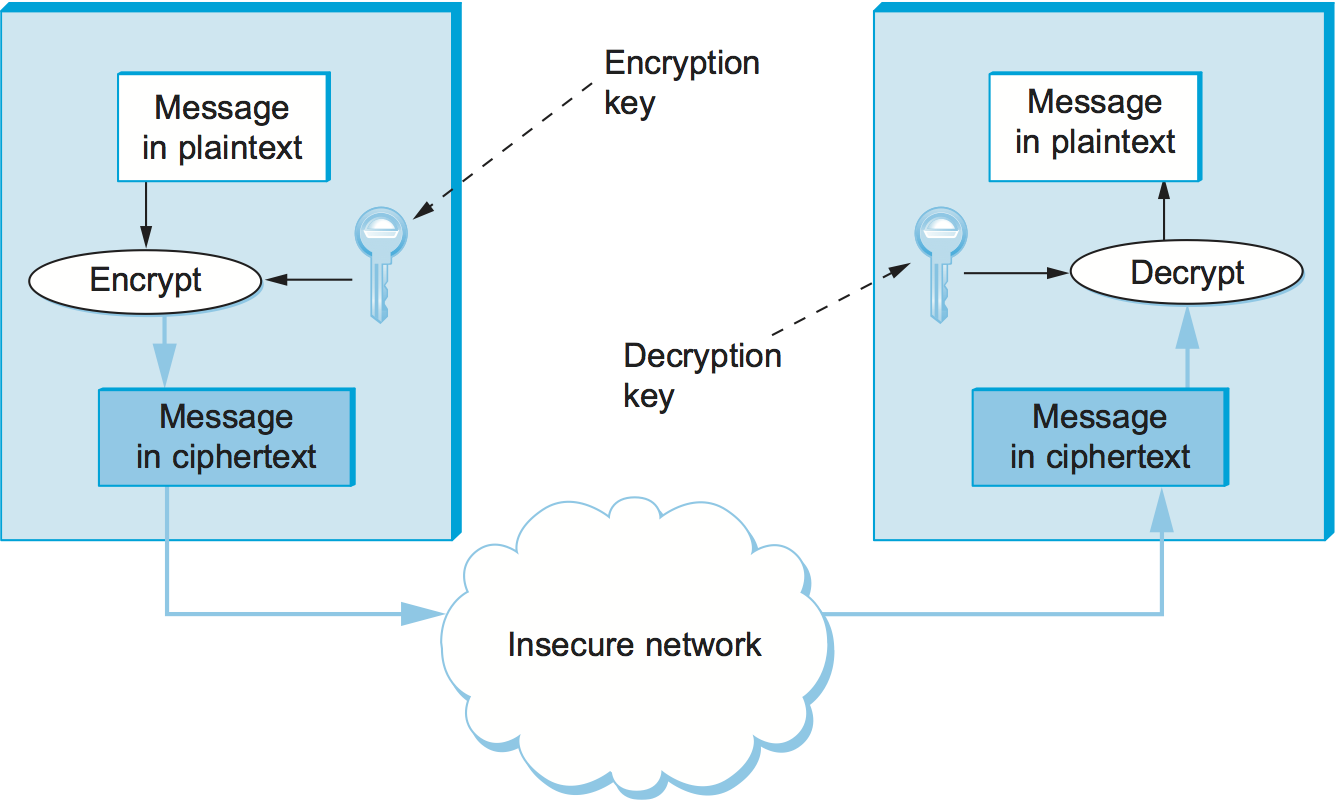

Encryption transforms a message in such a way that it becomes unintelligible to any party that does not have the secret of how to reverse the transformation. The sender applies an encryption function to the original plaintext message, resulting in a ciphertext message that is sent over the network, as shown in Figure 195. The receiver applies a secret decryption function—the inverse of the encryption function—to recover the original plaintext. The ciphertext transmitted across the network is unintelligible to any eavesdropper, assuming the eavesdropper doesn’t know the decryption function. The transformation represented by an encryption function and its corresponding decryption function is called a cipher.

Cryptographers have been led to the principle, first stated in 1883, that encryption and decryption functions should be parameterized by a key, and furthermore that the functions should be considered public knowledge—only the key need be secret. Thus, the ciphertext produced for a given plaintext message depends on both the encryption function and the key. One reason for this principle is that if you depend on the cipher being kept secret, then you have to retire the cipher (not just the keys) when you believe it is no longer secret. This means potentially frequent changes of cipher, which is problematic since it takes a lot of work to develop a new cipher. Also, one of the best ways to know that a cipher is secure is to use it for a long time—if no one breaks it, it’s probably secure. (Fortunately, there are plenty of people who will try to break ciphers and who will let it be widely known when they have succeeded, so no news is generally good news.) Thus, there is considerable cost and risk in deploying a new cipher. Finally, parameterizing a cipher with keys provides us with what is in effect a very large family of ciphers; by switching keys, we essentially switch ciphers, thereby limiting the amount of data that a cryptanalyst (code-breaker) can use to try to break our key/cipher and the amount she can read if she succeeds.

The basic requirement for an encryption algorithm is that it turn plaintext into ciphertext in such a way that only the intended recipient—the holder of the decryption key—can recover the plaintext. What this means is that encrypted messages cannot be read by people who do not hold the key.

It is important to realize that when a potential attacker receives a piece of ciphertext, he may have more information at his disposal than just the ciphertext itself. For example, he may know that the plaintext was written in English, which means that the letter e occurs more often in the plaintext that any other letter; the frequency of many other letters and common letter combinations can also be predicted. This information can greatly simplify the task of finding the key. Similarly, he may know something about the likely contents of the message; for example, the word “login” is likely to occur at the start of a remote login session. This may enable a known plaintext attack, which has a much higher chance of success than a ciphertext only attack. Even better is a chosen plaintext attack, which may be enabled by feeding some information to the sender that you know the sender is likely to transmit—such things have happened in wartime, for example.

The best cryptographic algorithms, therefore, can prevent the attacker from deducing the key even when the individual knows both the plaintext and the ciphertext. This leaves the attacker with no choice but to try all the possible keys—exhaustive, “brute force” search. If keys have n bits, then there are 2n possible values for a key (each of the n bits could be either a zero or a one). An attacker could be so lucky as to try the correct value immediately, or so unlucky as to try every incorrect value before finally trying the correct value of the key, having tried all 2n possible values; the average number of guesses to discover the correct value is halfway between those extremes, 2n/2. This can be made computationally impractical by choosing a sufficiently large key space and by making the operation of checking a key reasonably costly. What makes this difficult is that computing speeds keep increasing, making formerly infeasible computations feasible. Furthermore, although we are concentrating on the security of data as it moves through the network—that is, the data is sometimes vulnerable for only a short period of time—in general, security people have to consider the vulnerability of data that needs to be stored in archives for tens of years. This argues for a generously large key size. On the other hand, larger keys make encryption and decryption slower.

Most ciphers are block ciphers; they are defined to take as input a plaintext block of a certain fixed size, typically 64 to 128 bits. Using a block cipher to encrypt each block independently—known as electronic codebook (ECB) mode encryption—has the weakness that a given plaintext block value will always result in the same ciphertext block. Hence, recurring block values in the plaintext are recognizable as such in the ciphertext, making it much easier for a cryptanalyst to break the cipher.

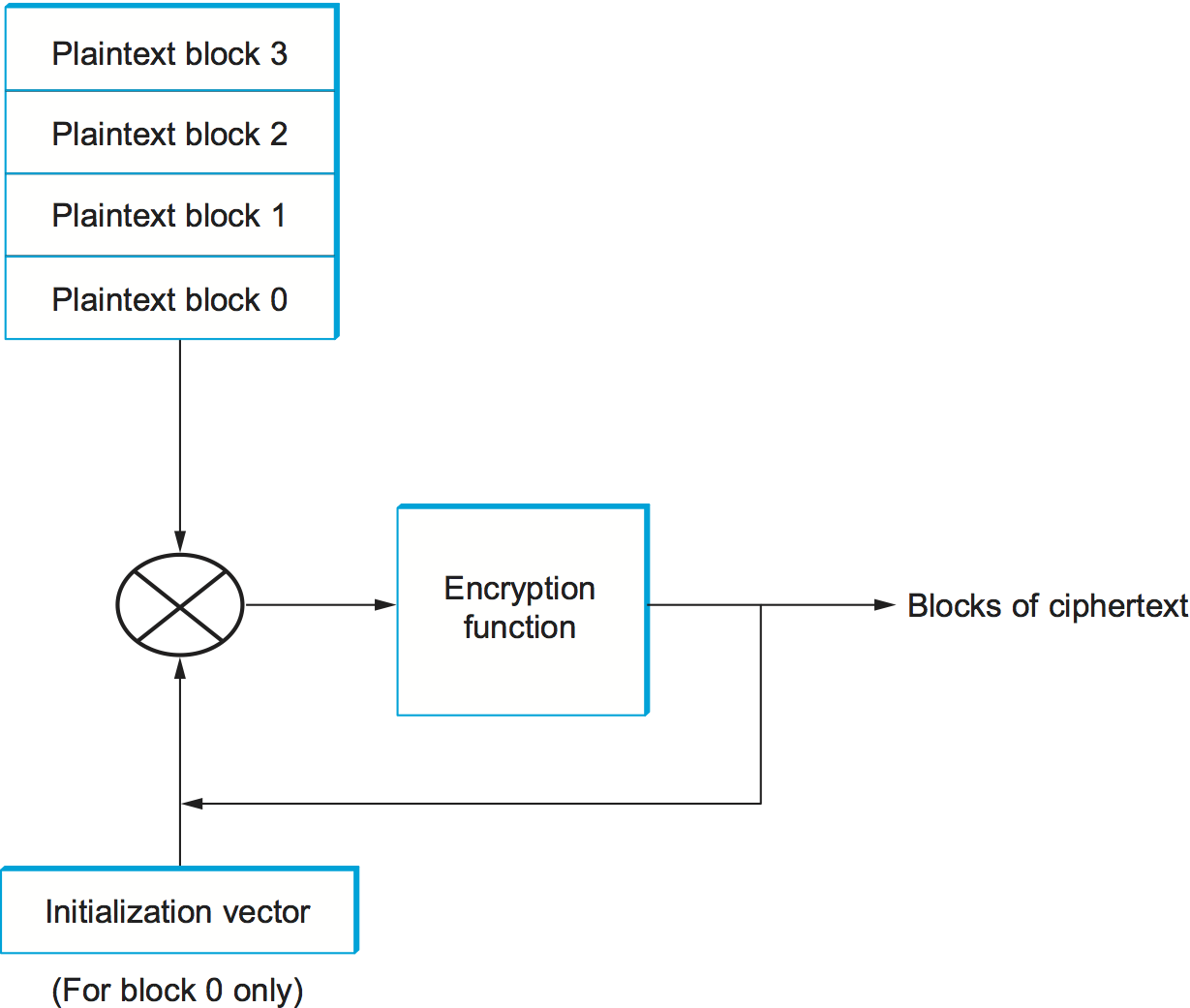

To prevent this, block ciphers are always augmented to make the ciphertext for a block vary depending on context. Ways in which a block cipher may be augmented are called modes of operation. A common mode of operation is cipher block chaining (CBC), in which each plaintext block is XORed with the previous block’s ciphertext before being encrypted. The result is that each block’s ciphertext depends in part on the preceding blocks (i.e., on its context). Since the first plaintext block has no preceding block, it is XORed with a random number. That random number, called an initialization vector (IV), is included with the series of ciphertext blocks so that the first ciphertext block can be decrypted. This mode is illustrated in Figure 196. Another mode of operation is counter mode, in which successive values of a counter (e.g., 1, 2, 3, \(\ldots\)) are incorporated into the encryption of successive blocks of plaintext.

Secret-Key Ciphers¶

In a secret-key cipher, both participants in a communication share the same key.[*] In other words, if a message is encrypted using a particular key, the same key is required for decrypting the message. If the cipher illustrated in Figure 195 were a secret-key cipher, then the encryption and decryption keys would be identical. Secret-key ciphers are also known as symmetric-key ciphers since the secret is shared with both participants. We’ll take a look at the alternative, public-key ciphers, shortly. (Public-key cipers are known as also asymmetric-key ciphers, since as we’ll soon se, the two participants use different keys.)

| [*] | We use the term participant for the parties involved in a secure communication since that is the term we have been using throughout the book to identify the two endpoints of a channel. In the security world, they are typically called principals. |

The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has issued standards for a series of secret-key ciphers. Data Encryption Standard (DES) was the first, and it has stood the test of time in that no cryptanalytic attack better than brute force search has been discovered. Brute force search, however, has gotten faster. DES’s keys (56 independent bits) are now too small given current processor speeds. DES keys have 56 independent bits (although they have 64 bits in total; the last bit of every byte is a parity bit). As noted above, you would, on average, have to search half of the space of 256 possible keys to find the right one, giving 255 = 3.6 × 1016 keys. That may sound like a lot, but such a search is highly parallelizable, so it’s possible to throw as many computers at the task as you can get your hands on—and these days it’s easy to lay your hands on thousands of computers. (Amazon will rent them to you for a few cents an hour.) By the late 1990s, it was already possible to recover a DES key after a few hours. Consequently, NIST updated the DES standard in 1999 to indicate that DES should only be used for legacy systems.

NIST also standardized the cipher Triple DES (3DES), which leverages the cryptanalysis resistance of DES while in effect increasing the key size. A 3DES key has 168 (= 3 × 56) independent bits, and is used as three DES keys; let’s call them DES-key1, DES-key2, and DES-key3. 3DES encryption of a block is performed by first DES encrypting the block using DES-key1, then DES decrypting the result using DES-key2, and finally DES encrypting that result using DES-key3. Decryption involves decrypting using DES-key3, then encrypting using DES-key2, then decrypting using DES-key1.

The reason 3DES encryption uses DES decryption with DES-key2 is to interoperate with legacy DES systems. If a legacy DES system uses a single key, then a 3DES system can perform the same encryption function by using that key for each of DES-key1, DES-key2, and DES-key3; in the first two steps, we encrypt and then decrypt with the same key, producing the original plaintext, which we then encrypt again.

Although 3DES solves DES’s key-length problem, it inherits some other shortcomings. Software implementations of DES/3DES are slow because it was originally designed by IBM for implementation in hardware. Also, DES/3DES uses a 64-bit block size; a larger block size is more efficient and more secure.

3DES is now being superseded by the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) standard issued by NIST. The cipher underlying AES (with a few minor modifications) was originally named Rijndael (pronounced roughly like “Rhine dahl”) based on the names of its inventors, Daemen and Rijmen. AES supports key lengths of 128, 192, or 256 bits, and the block length is 128 bits. AES permits fast implementations in both software and hardware. It doesn’t require much memory, which makes it suitable for small mobile devices. AES has some mathematically proven security properties and, as of the time of writing, has not suffered from any significant successful attacks.

Public-Key Ciphers¶

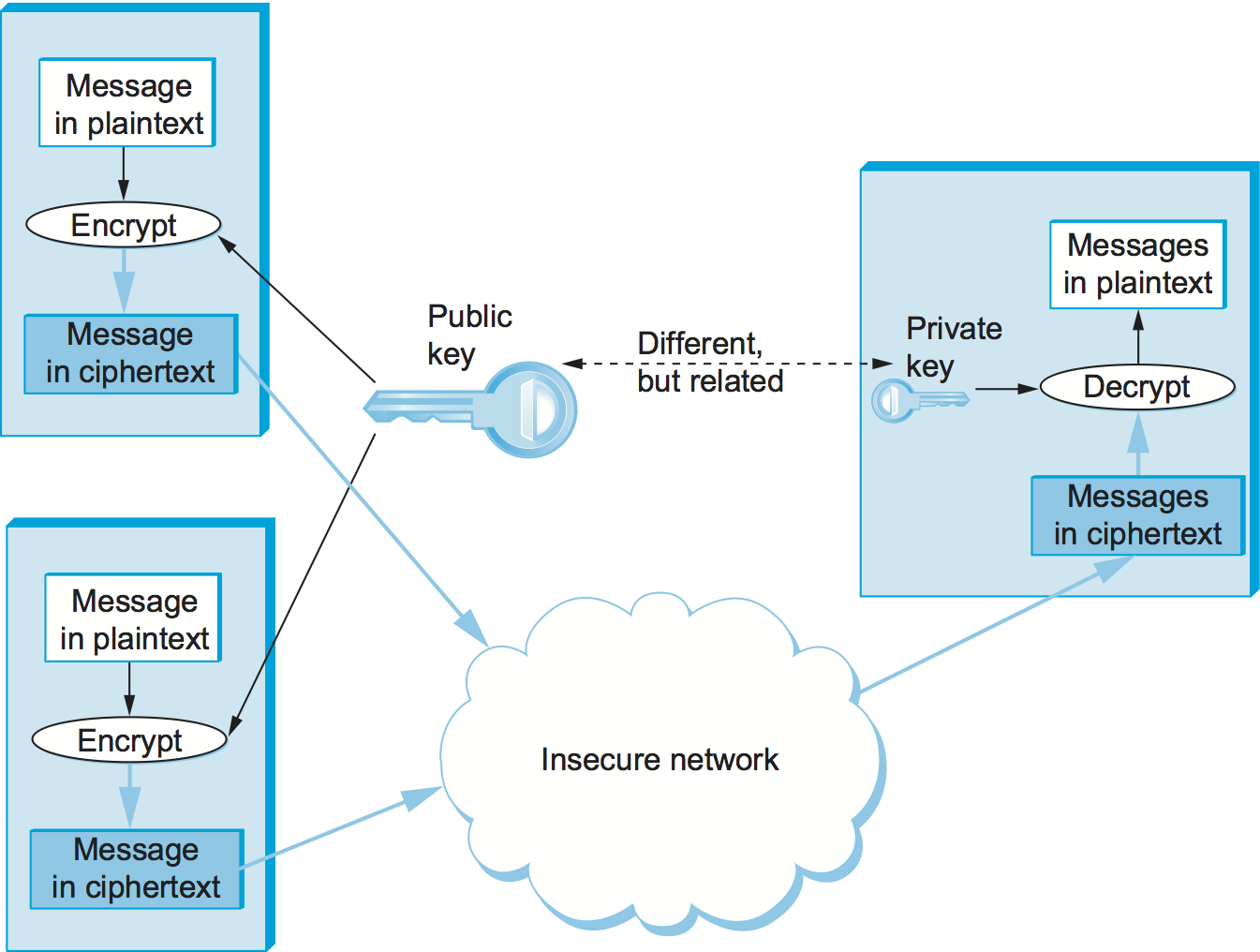

An alternative to secret-key ciphers is public-key, ciphers. Instead of a single key shared by two participants, a public-key cipher uses a pair of related keys, one for encryption and a different one for decryption. The pair of keys is “owned” by just one participant. The owner keeps the decryption key secret so that only the owner can decrypt messages; that key is called the private key. The owner makes the encryption key public, so that anyone can encrypt messages for the owner; that key is called the public key. Obviously, for such a scheme to work, it must not be possible to deduce the private key from the public key. Consequently, any participant can get the public key and send an encrypted message to the owner of the keys, and only the owner has the private key necessary to decrypt it. This scenario is depicted in Figure 197.

Because it is somewhat unintuitive, we emphasize that the public encryption key is useless for decrypting a message—you couldn’t even decrypt a message that you yourself had just encrypted unless you had the private decryption key. If we think of keys as defining a communication channel between participants, then another difference between public-key and secret-key ciphers is the topology of the channels. A key for a secret-key cipher provides a channel that is two-way between two participants—each participant holds the same (symmetric) key that either one can use to encrypt or decrypt messages in either direction. A public/private key pair, in contrast, provides a channel that is one way and many-to-one: from everyone who has the public key to the unique owner of the private key, as illustrated in Figure 197.

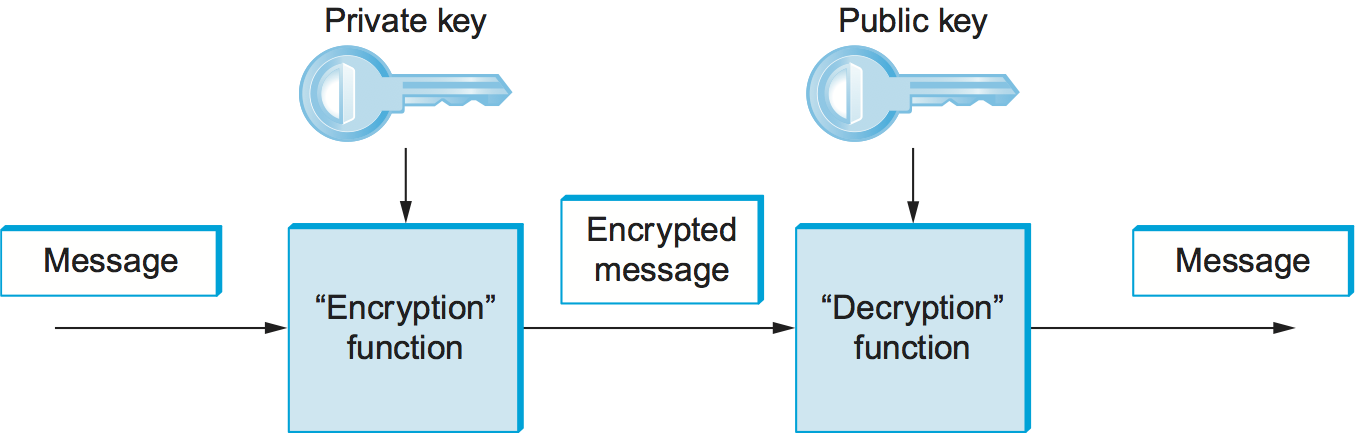

An important additional property of public-key ciphers is that the private “decryption” key can be used with the encryption algorithm to encrypt messages so that they can only be decrypted using the public “encryption” key. This property clearly wouldn’t be useful for confidentiality since anyone with the public key could decrypt such a message. (Indeed, for two-way confidentiality between two participants, each participant needs its own pair of keys, and each encrypts messages using the other’s public key.) This property is, however, useful for authentication since it tells the receiver of such a message that it could only have been created by the owner of the keys (subject to certain assumptions that we will get into later). This is illustrated in Figure 198. It should be clear from the figure that anyone with the public key can decrypt the encrypted message, and, assuming that the result of the decryption matches the expected result, it can be concluded that the private key must have been used to perform the encryption. Exactly how this operation is used to provide authentication is the topic of a later section. As we will see, public-key ciphers are used primarily for authentication and to confidentially distribute secret (symmetric) keys, leaving the rest of confidentiality to secret-key ciphers.

A bit of interesting history: The concept of public-key ciphers was first published in 1976 by Diffie and Hellman. Subsequently, however, documents have come to light proving that Britain’s Communications-Electronics Security Group had discovered public-key ciphers by 1970, and the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) claims to have discovered them in the mid-1960s.

The best-known public-key cipher is RSA, named after its inventors: Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman. RSA relies on the high computational cost of factoring large numbers. The problem of finding an efficient way to factor numbers is one that mathematicians have worked on unsuccessfully since long before RSA appeared in 1978, and RSA’s subsequent resistance to cryptanalysis has further bolstered confidence in its security. Unfortunately, RSA needs relatively large keys, at least 1024 bits, to be secure. This is larger than keys for secret-key ciphers because it is faster to break an RSA private key by factoring the large number on which the pair of keys is based than by exhaustively searching the key space.

Another public-key cipher is ElGamal. Like RSA, it relies on a mathematical problem, the discrete logarithm problem, for which no efficient solution has been found, and requires keys of at least 1024 bits. There is a variation of the discrete logarithm problem, arising when the input is an elliptic curve, that is thought to be even more difficult to compute; cryptographic schemes based on this problem are referred to as elliptic curve cryptography.

Public-key ciphers are, unfortunately, several orders of magnitude slower than secret-key ciphers. Consequently, secret-key ciphers are used for the vast majority of encryption, while public-key ciphers are reserved for use in authentication and session key establishment.

Authenticators¶

Encryption alone does not provide data integrity. For example, just randomly modifying a ciphertext message could turn it into something that decrypts into valid-looking plaintext, in which case the tampering would be undetectable by the receiver. Nor does encryption alone provide authentication. It is not much use to say that a message came from a certain participant if the contents of the message have been modified after that participant created it. In a sense, integrity and authentication are fundamentally inseparable.

An authenticator is a value, to be included in a transmitted message, that can be used to verify simultaneously the authenticity and the data integrity of a message. We will see how authenticators can be used in protocols. For now, we focus on the algorithms that produce authenticators.

You may recall that checksums and cyclic redundancy checks (CRCs) are pieces of information added to a message so the receiver detect when the message has been inadvertently modified by bit errors. A similar concept applies to authenticators, with the added challenge that the corruption of the message is likely to be deliberately performed by someone who wants the corruption to go undetected. To support authentication, an authenticator includes some proof that whoever created the authenticator knows a secret that is known only to the alleged sender of the message; for example, the secret could be a key, and the proof could be some value encrypted using the key. There is a mutual dependency between the form of the redundant information and the form of the proof of secret knowledge. We discuss several workable combinations.

We initially assume that the original message need not be confidential—that a transmitted message will consist of the plaintext of the original message plus an authenticator. Later we will consider the case where confidentiality is desired.

One kind of authenticator combines encryption and a cryptographic hash function. Cryptographic hash algorithms are treated as public knowledge, as with cipher algorithms. A cryptographic hash function (also known as a cryptographic checksum) is a function that outputs sufficient redundant information about a message to expose any tampering. Just as a checksum or CRC exposes bit errors introduced by noisy links, a cryptographic checksum is designed to expose deliberate corruption of messages by an adversary. The value it outputs is called a message digest and, like an ordinary checksum, is appended to the message. All the message digests produced by a given hash have the same number of bits regardless of the length of the original message. Since the space of possible input messages is larger than the space of possible message digests, there will be different input messages that produce the same message digest, like collisions in a hash table.

An authenticator can be created by encrypting the message digest. The receiver computes a digest of the plaintext part of the message and compares that to the decrypted message digest. If they are equal, then the receiver would conclude that the message is indeed from its alleged sender (since it would have to have been encrypted with the right key) and has not been tampered with. No adversary could get away with sending a bogus message with a matching bogus digest because she would not have the key to encrypt the bogus digest correctly. An adversary could, however, obtain the plaintext original message and its encrypted digest by eavesdropping. The adversary could then (since the hash function is public knowledge) compute the digest of the original message and generate alternative messages looking for one with the same message digest. If she finds one, she could undetectably send the new message with the old authenticator. Therefore, security requires that the hash function have the one-way property: It must be computationally infeasible for an adversary to find any plaintext message that has the same digest as the original.

For a hash function to meet this requirement, its outputs must be fairly randomly distributed. For example, if digests are 128 bits long and randomly distributed, then you would need to try 2127 messages, on average, before finding a second message whose digest matches that of a given message. If the outputs are not randomly distributed—that is, if some outputs are much more likely than others—then for some messages you could find another message with the same digest much more easily than this, which would reduce the security of the algorithm. If you were instead just trying to find any collision—any two messages that produce the same digest—then you would need to compute the digests of only 264 messages, on average. This surprising fact is the basis of the “birthday attack”—see the exercises for more details.

There have been several common cryptographic hash algorithms over the years, including Message Digest 5 (MD5) and the Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA) family. Weaknesses of MD5 and earlier versions of SHA have been known for some time, which led NIST to recommend using SHA-3 in 2015. generating an encrypted message digest, the digest encryption could use either a secret-key cipher or a public-key cipher. If a public-key cipher is used, the digest would be encrypted using the sender’s private key (the one we normally think of as being used for decryption), and the receiver—or anyone else—could decrypt the digest using the sender’s public key.

A digest encrypted with a public key algorithm but using the private key is called a digital signature because it provides nonrepudiation like a written signature. The receiver of a message with a digital signature can prove to any third party that the sender really sent that message, because the third party can use the sender’s public key to check for herself. (secret-key encryption of a digest does not have this property because only the two participants know the key; furthermore, since both participants know the key, the alleged receiver could have created the message herself.) Any public-key cipher can be used for digital signatures. Digital Signature Standard (DSS) is a digital signature format that has been standardized by NIST. DSS signatures may use any one of three public-key ciphers, one based on RSA, another on ElGamal, and a third called the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm.

Another kind of authenticator is similar, but instead of encrypting a hash it uses a hash-like function that takes a secret value (known only to the sender and the receiver) as a parameter, as illustrated in Figure 199. Such a function outputs an authenticator called a message authentication code (MAC). The sender appends the MAC to her plaintext message. The receiver recomputes the MAC using the plaintext and the secret value and compares that recomputed MAC to the received MAC.

A common variation on MACs is to apply a cryptographic hash (such as MD5 or SHA-1) to the concatenation of the plaintext message and the secret value, as illustrated in Figure 199. The resulting digest is called a hashed message authentication code (HMAC) since it is essentially a MAC. The HMAC, but not the secret value, is appended to the plaintext Only a receiver who knows the secret value can compute the correct HMAC to compare with the received HMAC. If it weren’t for the one-way property of the hash, an adversary might be able to find the input that generated the HMAC and compare it to the plaintext message to determine the secret value.

Up to this point, we have been assuming that the message wasn’t confidential, so the original message could be transmitted as plaintext. To add confidentiality to a message with an authenticator, it suffices to encrypt the concatenation of the entire message including its authenticator—the MAC, HMAC, or encrypted digest. Remember that, in practice, confidentiality is implemented using secret-key ciphers because they are so much faster than public-key ciphers. Furthermore, it costs little to include the authenticator in the encryption, and it increases security. A common simplification is to encrypt the message with its (raw) digest, such that the digest is only encrypted once; in this case, the entire ciphertext message is considered to be an authenticator.

Although authenticators may seem to solve the authentication problem, we will see in a later section that they are only the foundation of a solution. First, however, we address the issue of how participants obtain keys in the first place.