8.4 Authentication Protocols¶

So far we described how to encrypt messages, build authenticators, predistribute the necessary keys. It might seem as if all we have to do to make a protocol secure is append an authenticator to every message and, if we want confidentiality, encrypt the message.

There are two main reasons why it’s not that simple. First, there is the problem of a replay attack: an adversary retransmitting a copy of a message that was previously sent. If the message was an order you had placed on a website, for example, then the replayed message would appear to the website as though you had ordered more of the same. Even though it wasn’t the original incarnation of the message, its authenticator would still be valid; after all, the message was created by you, and it wasn’t modified. Clearly, we need a solution that ensures originality.

In a variation of this attack called a suppress-replay attack, an adversary might merely delay your message (by intercepting and later replaying it), so that it is received at a time when it is no longer appropriate. For example, an adversary could delay your order to buy stock from an auspicious time to a time when you would not have wanted to buy. Although this message would in a sense be the original, it wouldn’t be timely. So we also need to ensure timeliness. Originality and timeliness may be considered aspects of integrity. Ensuring them will in most cases require a nontrivial, back-and-forth protocol.

The second problem we have not yet solved is how to establish a session key. A session key is a secret-key cipher key generated on the fly and used for just one session. This too involves a nontrivial protocol.

What these two issues have in common is authentication. If a message is not original and timely, then from a practical standpoint we want to consider it as not being authentic, not being from whom it claims to be. And, obviously, when you are arranging to share a new session key with someone, you want to know you are sharing it with the right person. Usually, authentication protocols establish a session key at the same time, so that at the end of the protocol Alice and Bob have authenticated each other and they have a new secret key to use. Without a new session key, the protocol would just authenticate Alice and Bob at one point in time; a session key allows them to efficiently authenticate subsequent messages. Generally, session key establishment protocols perform authentication (a notable exception is Diffie-Hellman, as described below, so the terms authentication protocol and session key establishment protocol are almost synonymous.

There is a core set of techniques used to ensure originality and timeliness in authentication protocols. We describe those techniques before moving on to particular protocols.

Originality and Timeliness Techniques¶

We have seen that authenticators alone do not enable us to detect messages that are not original or timely. One approach is to include a timestamp in the message. Obviously the timestamp itself must be tamperproof, so it must be covered by the authenticator. The primary drawback to timestamps is that they require distributed clock synchronization. Since our system would then depend on synchronization, the clock synchronization itself would need to be defended against security threats, in addition to the usual challenges of clock synchronization. Another issue is that distributed clocks are synchronized to only a certain degree—a certain margin of error. Thus, the timing integrity provided by timestamps is only as good as the degree of synchronization.

Another approach is to include a nonce—a random number used only once—in the message. Participants can then detect replay attacks by checking whether a nonce has been used previously. Unfortunately, this requires keeping track of past nonces, of which a great many could accumulate. One solution is to combine the use of timestamps and nonces, so that nonces are required to be unique only within a certain span of time. That makes ensuring uniqueness of nonces manageable while requiring only loose synchronization of clocks.

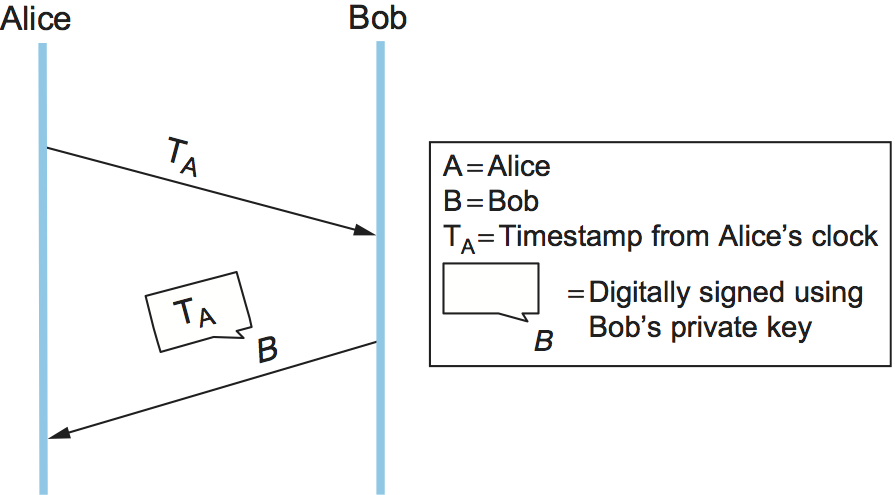

Another solution to the shortcomings of timestamps and nonces is to use one or both of them in a challenge-response protocol. Suppose we use a timestamp. In a challenge-response protocol, Alice sends Bob a timestamp, challenging Bob to encrypt it in a response message (if they share a secret key) or digitally sign it in a response message (if Bob has a public key, as in Figure 202). The encrypted timestamp is like an authenticator that additionally proves timeliness. Alice can easily check the timeliness of the timestamp in a response from Bob since that timestamp comes from Alice’s own clock—no distributed clock synchronization needed. Suppose instead that the protocol uses nonces. Then Alice need only keep track of those nonces for which responses are currently outstanding and haven’t been outstanding too long; any purported response with an unrecognized nonce must be bogus.

The beauty of challenge-response, which might otherwise seem excessively complex, is that it combines timeliness and authentication; after all, only Bob (and possibly Alice, if it’s a secret-key cipher) knows the key necessary to encrypt the never before seen timestamp or nonce. Timestamps or nonces are used in most of the authentication protocols that follow.

Public-Key Authentication Protocols¶

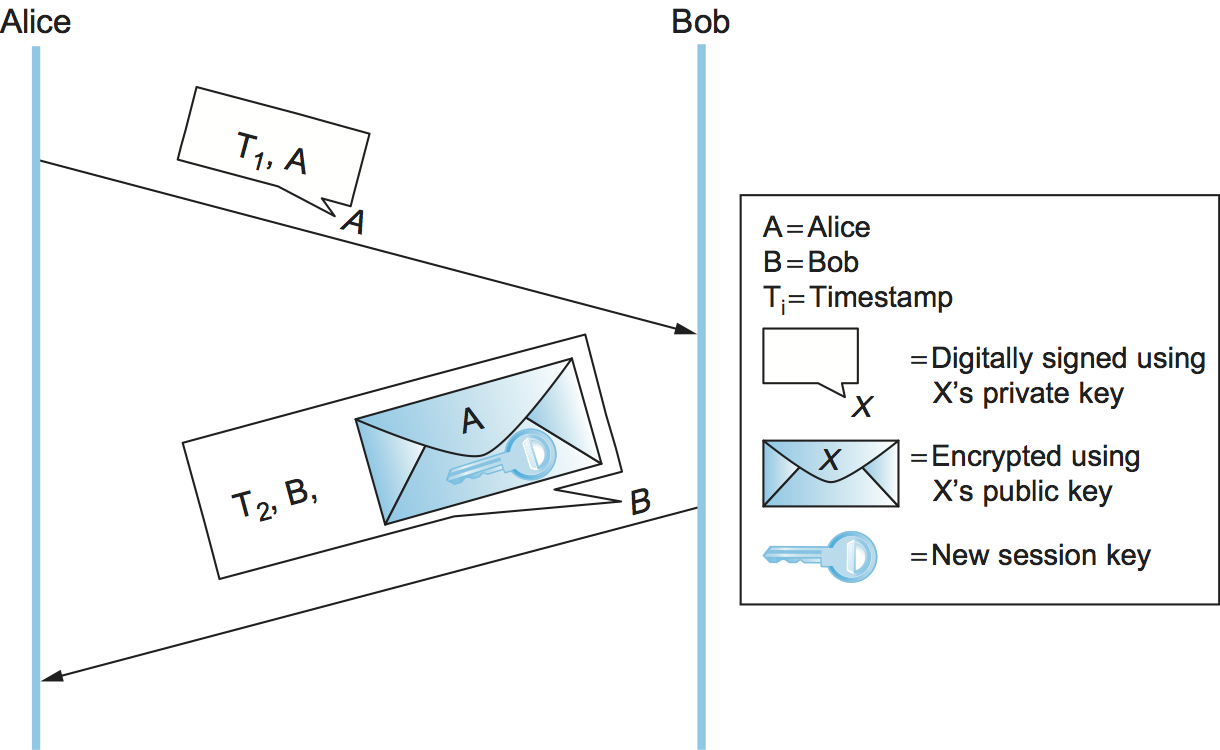

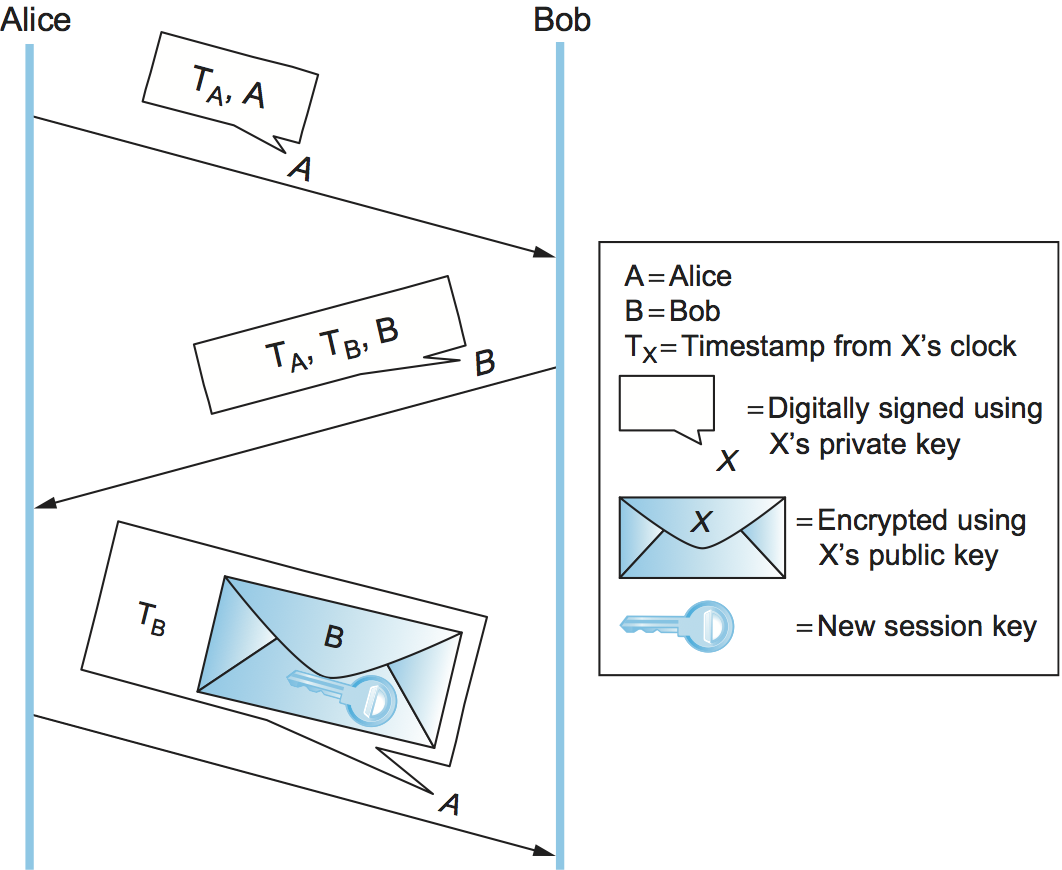

In the following discussion, we assume that Alice and Bob’s public keys have been predistributed to each other via some means such as a PKI. We mean this to include the case where Alice includes her certificate in her first message to Bob, and the case where Bob searches for a certificate about Alice when he receives her first message.

This first protocol (Figure 203) relies on Alice and Bob’s clocks being synchronized. Alice sends Bob a message with a timestamp and her identity in plaintext plus her digital signature. Bob uses the digital signature to authenticate the message and the timestamp to verify its freshness. Bob sends back a message with a timestamp and his identity in plaintext, as well as a new session key encrypted (for confidentiality) using Alice’s public key, all digitally signed. Alice can verify the authenticity and freshness of the message, so she knows she can trust the new session key. To deal with imperfect clock synchronization, the timestamps could be augmented with nonces.

The second protocol (Figure 204) is similar but does not rely on clock synchronization. In this protocol, Alice again sends Bob a digitally signed message with a timestamp and her identity. Because their clocks aren’t synchronized, Bob cannot be sure that the message is fresh. Bob sends back a digitally signed message with Alice’s original timestamp, his own new timestamp, and his identity. Alice can verify the freshness of Bob’s reply by comparing her current time against the timestamp that originated with her. She then sends Bob a digitally signed message with his original timestamp and a new session key encrypted using Bob’s public key. Bob can verify the freshness of the message because the timestamp came from his clock, so he knows he can trust the new session key. The timestamps essentially serve as convenient nonces, and indeed this protocol could use nonces instead.

Secret-Key Authentication Protocols¶

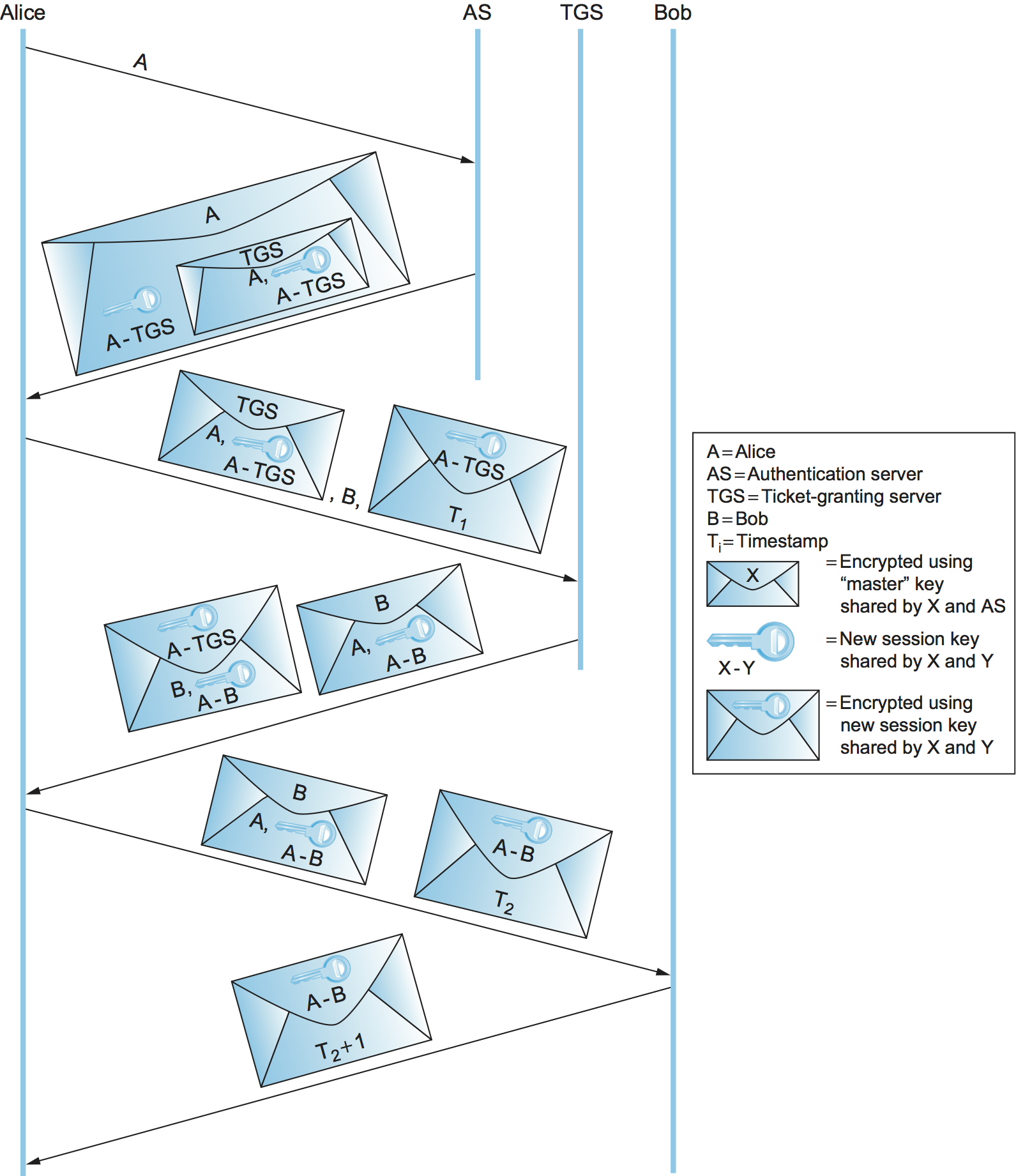

Only in fairly small systems is it practical to predistribute secret keys to every pair of entities. We focus here on larger systems, where each entity would have its own master key shared only with a Key Distribution Center (KDC). In this case, secret-key-based authentication protocols involve three parties: Alice, Bob, and a KDC. The end product of the authentication protocol is a session key shared between Alice and Bob that they will use to communicate directly, without involving the KDC.

The Needham-Schroeder authentication protocol is illustrated in Figure 205. Note that the KDC doesn’t actually authenticate Alice’s initial message and doesn’t communicate with Bob at all. Instead, the KDC uses its knowledge of Alice’s and Bob’s master keys to construct a reply that would be useless to anyone other than Alice (because only Alice can decrypt it) and contains the necessary ingredients for Alice and Bob to perform the rest of the authentication protocol themselves.

The nonce in the first two messages is to assure Alice that the KDC’s reply is fresh. The second and third messages include the new session key and Alice’s identifier, encrypted together using Bob’s master key. It is a sort of secret-key version of a public-key certificate; it is in effect a signed statement by the KDC (because the KDC is the only entity besides Bob who knows Bob’s master key) that the enclosed session key is owned by Alice and Bob. Although the nonce in the last two messages is intended to assure Bob that the third message was fresh, there is a flaw in this reasoning.

Kerberos¶

Kerberos is an authentication system based on the Needham-Schroeder protocol and specialized for client/server environments. Originally developed at MIT, it has been standardized by the IETF and is available as both open source and commercial products. We will focus here on some of Kerberos’s interesting innovations.

Kerberos clients are generally human users, and users authenticate themselves using passwords. Alice’s master key, shared with the KDC, is derived from her password—if you know the password, you can compute the key. Kerberos assumes anyone can physically access any client machine; therefore, it is important to minimize the exposure of Alice’s password or master key not just in the network but also on any machine where she logs in. Kerberos takes advantage of Needham-Schroeder to accomplish this. In Needham-Schroeder, the only time Alice needs to use her password is when decrypting the reply from the KDC. Kerberos client-side software waits until the KDC’s reply arrives, prompts Alice to enter her password, computes the master key and decrypts the KDC’s reply, and then erases all information about the password and master key to minimize its exposure. Also note that the only sign a user sees of Kerberos is when the user is prompted for a password.

In Needham-Schroeder, the KDC’s reply to Alice plays two roles: It gives her the means to prove her identity (only Alice can decrypt the reply), and it gives her a sort of secret-key certificate or “ticket” to present to Bob—the session key and Alice’s identifier, encrypted with Bob’s master key. In Kerberos, those two functions—and the KDC itself, in effect—are split up (Figure 206). A trusted server called an Authentication Server (AS) plays the first KDC role of providing Alice with something she can use to prove her identity—not to Bob this time, but to a second trusted server called a Ticket Granting Server (TGS). The TGS plays the second KDC role, replying to Alice with a ticket she can present to Bob. The attraction of this scheme is that if Alice needs to communicate with several servers, not just Bob, then she can get tickets for each of them from the TGS without going back to the AS.

In the client/server application domain for which Kerberos is intended, it is reasonable to assume a degree of clock synchronization. This allows Kerberos to use timestamps and lifespans instead of Needham-Shroeder’s nonces, and thereby eliminate the Needham-Schroeder security weakness. Kerberos supports a choice of hash functions and secret-key ciphers, allowing it to keep pace with the state-of-the-art in cryptographic algorithms.